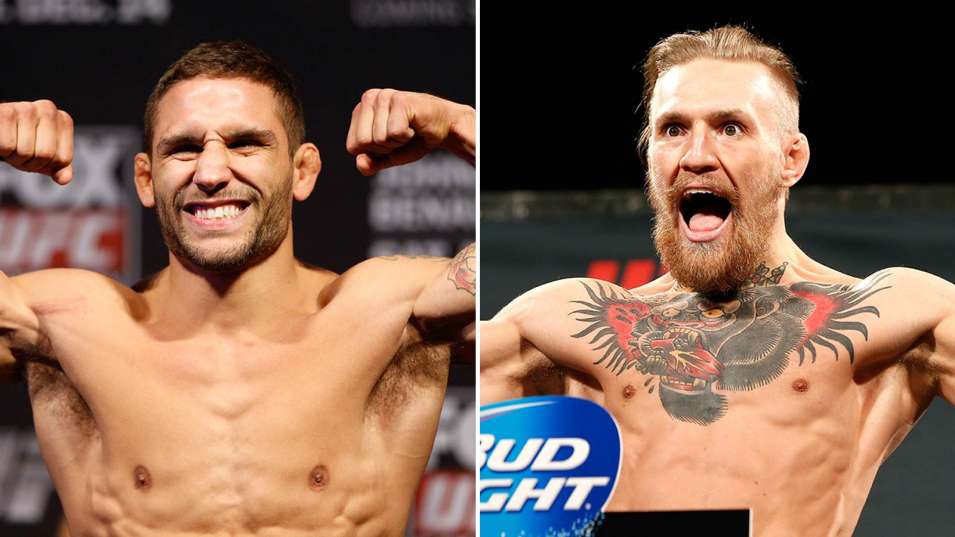

For what it’s worth, I have a newfound respect for Conor McGregor. He lost a fair fight and refused to blame it on the step up in weight classes (which would have been bogus) or being unprepared (he had a fantastic game plan). I still think he’s allowed Dana White to steer him away from his toughest match ups, but the world was waiting to see him fall and he’s handled it with relative grace.

So kudos Mr. McGregor.

On the other hand, every potential opponent for Conor McGregor (whom were not too kind via Twitter I may add) watched that fight and salivated.

1) McGregor is a man with a plan

In my previous article, I mentioned that because McGregor gave up reach and height to Nate Diaz his traditional style of fighting from the outside would be null and void. But I did suggest that because both fighters were southpaws, McGregor would have an opportunity to cross counter over the top of Nate Diaz’s jab.

Instead of countering, McGregor simply stepped in and threw his left over the top as hard as he could at every opportunity and found tremendous success.

Unlike his older brother Nick, Nate Diaz is a less dexterous puncher which leaves him with a dearth of offensive options from either side. McGregor (correctly) did the math and realized he could step in deep and smash Nate over the top whenever he wanted. As a result he rocked the notoriously durable Diaz on multiple occasions and left him looking like an extra in a horror movie.

Eventually the reach disadvantage was his undoing but watching McGregor adapt such a great game on short notice against an opponent with a build which, if he stays at featherweight, he will never encounter again was incredible.

It means that every single opponent will face a different Conor McGregor, a frightening prospect to say the least.

2) McGregor is defensively flawed

To be fair, it’s not all his fault.

McGregor has spent the overwhelming majority of his career (I would say whole, but some of his opponents are difficult to look up) fighting with a reach advantage. So on the few occasions during which he was hit hard, he could usually get away and recover. It’s easy to make it a habit.

Against Diaz, he had no such luxury and he really paid for it. Rather than being able to skip away and fire the occasional counter punch, McGregor instead found himself eating jabs, straights and hooks at will and accumulated tremendous damage.

While there aren’t many fighters who can out-range McGregor, it means that if you can ring his bell you have a great chance of beating him.

This is a significant factor when considering McGregor’s most anticipated superfight: lightweight juggernaut Rafael Dos Anjos.

What people often forget about Dos Anjos while drooling over his unbelievable streak over elite competition is that he’s a pretty small lightweight. Sure he’s muscular, but in a sport in which the athletes just keep getting bigger and bigger (Pettis, Cerrone, Diaz, Ferguson, Khabib, etc.) he stands at a paltry 5’ 8” with a 70” reach. Yet he specializes in safely getting past his opponent’s reach and nailing them with his ramrod of a left cross before working them over until they’re no longer eligible for organ donation.

Could McGregor still knock him out? Hell yes; you don’t go 7-1 in the UFC with 6 knockouts without doing something right. But if Rafael Dos Anjos lands one clean punch, the nature of the fight will change completely.

And that’s something every future McGregor opponent must consider.

3) McGregor MAY have a gas tank issue

This is theoretical, but stick with me.

McGregor weighed in at 168, which is 2lbs less than the welterweight limit. The change of weight class also happened in only 11 days, and there’s no legal way to pack on a significant amount of muscle in that time period. With those two factors considered, it’s safe to assume that we got the most hydrated, physically fit Conor McGregor we’d ever seen.

Yet, by the second round, he had visibly slowed down. He still had bricks for hands but he was moving like someone had filled his ankles with cement. Nate Diaz hit him with crisp, long punches but he was also able to hit the Irishman as he exited the clinch on multiple occasions because he simply couldn’t get away in time.

At featherweight, this was understandable.

For all the complaining fighters like Jose Aldo do about weight cuts, it’s hard to name a featherweight with a more brutal weight cut than Conor McGregor. Remember that this guy is 5’ 9” with a 74” reach; he’s freaking gigantic. So seeing him tire visibly in the second round against Chad Mendes was understandable.

But watching it happened at welterweight? That raises some questions.

McGregor’s style is extremely taxing. It involves being able to accelerate and decelerate, leap in and out and swing with extraordinary speed and timing. If you want to see why interval training is fantastic for conditioning, run a steady lap around a track and then try doing it at sprint intervals and see which one winds you more. Re-watching the Chad Mendes fight, I realized that McGregor’s ability to throw smooth combinations on offense disguised the fact that his feet were rapidly fading.

Could his featherweight fatigue be from his weight cut and the welterweight fatigue be from an adrenaline dump on the big stage? Of course! After all, McGregor is a confident fighter but he’s only human.

But we must also consider the possibility that if a fighter can make McGregor work for a round, their chances of winning skyrocket.

The key word there is work. Max Holloway went the distance with McGregor but was psychologically broken and couldn’t mount much of an offense. As a result the McGregor was able to have his way with him for 3 full rounds.

But say that a fighter can take him down once (like Mendes) or defend against a flurry (like Diaz) or sink some deep body shots (like RDA will) . . . McGregor may become that much more beatable in the subsequent rounds. He’ll still have knock out power but the feints, baits and counters that make him so lethal will erode leaving him a dangerous but far more predictable fighter.

But like I said, he’s 7-1 in the UFC with 6 KOs. Easier said than done.